Muscular dystrophy

(Redirected from Myodystrophy)

Editor-In-Chief: Prab R Tumpati, MD

Obesity, Sleep & Internal medicine

Founder, WikiMD Wellnesspedia &

W8MD medical weight loss NYC and sleep center NYC

| Muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synonyms | N/A |

| Pronounce | N/A |

| Specialty | N/A |

| Symptoms | Progressive muscle weakness, muscle wasting |

| Complications | Cardiomyopathy, respiratory failure, scoliosis |

| Onset | Childhood or adulthood, depending on type |

| Duration | Long term |

| Types | Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Becker muscular dystrophy, Myotonic dystrophy, Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, Congenital muscular dystrophy, Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, Distal muscular dystrophy, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy |

| Causes | Genetic mutation |

| Risks | Family history |

| Diagnosis | Genetic testing, muscle biopsy, electromyography |

| Differential diagnosis | Spinal muscular atrophy, myopathy, motor neuron disease |

| Prevention | N/A |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, orthopedic devices, medications |

| Medication | Corticosteroids, heart medications |

| Prognosis | Varies by type; some forms lead to early death |

| Frequency | 1 in 5,000 males (Duchenne) |

| Deaths | N/A |

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The first historical account of muscular dystrophy appeared in 1830, when Sir Charles Bell wrote an essay about an illness that caused progressive weakness in boys. Six years later, another scientist reported on two brothers who developed generalized weakness, muscle damage, and replacement of damaged muscle tissue with fat and connective tissue. At that time the symptoms were thought to be signs of tuberculosis.

In the 1850s, descriptions of boys who grew progressively weaker, lost the ability to walk, and died at an early age became more prominent in medical journals. In the following decade, French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne gave a comprehensive account of 13 boys with the most common and severe form of the disease (which now carries his name— Duchenne muscular dystrophy). It soon became evident that the disease had more than one form, and that these diseases affected people of either sex and of all ages.

What is muscular dystrophy?[edit | edit source]

Muscular dystrophy (MD) refers to a group of more than 30 genetic diseases that cause progressive weakness and degeneration of skeletal muscles used during voluntary movement. The word dystrophy is derived from the Greek dys, which means "difficult" or "faulty," and troph, or "nourish." These disorders vary in age of onset, severity, and pattern of affected muscles. All forms of MD grow worse as muscles progressively degenerate and weaken. Many individuals eventually lose the ability to walk. Some types of MD also affect the heart, gastrointestinal system, endocrine glands, spine, eyes, brain, and other organs. Respiratory and cardiac diseases may occur, and some people may develop a swallowing disorder. MD is not contagious and cannot be brought on by injury or activity.

What causes MD?[edit | edit source]

All of the muscular dystrophies are inherited and involve a mutation in one of the thousands of genes that program proteins critical to muscle integrity. The body's cells don't work properly when a protein is altered or produced in insufficient quantity (or sometimes missing completely). Many cases of MD occur from spontaneous mutations that are not found in the genes of either parent, and this defect can be passed to the next generation. Genes are like blueprints: they contain coded messages that determine a person's characteristics or traits. They are arranged along 23 rod-like pairs of chromosomes, * with one half of each pair being inherited from each parent. Each half of a chromosome pair is similar to the other, except for one pair, which determines the sex of the individual. Muscular dystrophies can be inherited in three ways:

- Autosomal dominant inheritance occurs when a child receives a normal gene from one parent and a defective gene from the other parent. Autosomal means the genetic mutation can occur on any of the 22 non-sex chromosomes in each of the body's cells. Dominant means only one parent needs to pass along the abnormal gene in order to produce the disorder. In families where one parent carries a defective gene, each child has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the gene and therefore the disorder. Males and females are equally at risk and the severity of the disorder can differ from person to person.

- Autosomal recessive inheritance means that both parents must carry and pass on the faulty gene. The parents each have one defective gene but are not affected by the disorder. Children in these families have a 25 percent chance of inheriting both copies of the defective gene and a 50 percent chance of inheriting one gene and therefore becoming a carrier, able to pass along the defect to their children. Children of either sex can be affected by this pattern of inheritance.

- X-linked (or sex-linked) recessive inheritance occurs when a mother carries the affected gene on one of her two X chromosomes and passes it to her son (males always inherit an X chromosome from their mother and a Y chromosome from their father, while daughters inherit an X chromosome from each parent). Sons of carrier mothers have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the disorder. Daughters also have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the defective gene but usually are not affected, since the healthy X chromosome they receive from their father can offset the faulty one received from their mother. Affected fathers cannot pass an X-linked disorder to their sons but their daughters will be carriers of that disorder. Carrier females occasionally can exhibit milder symptoms of MD.

*Terms in Italics are defined in the glossary.

How many people have MD?[edit | edit source]

MD occurs worldwide, affecting all races. Its incidence varies, as some forms are more common than others. Its most common form in children, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, affects approximately 1 in every 3,500 to 6,000 male births each year in the United States. Some types of MD are more prevalent in certain countries and regions of the world. Many muscular dystrophies are familial, meaning there is some family history of the disease. Duchenne cases often have no prior family history. This is likely due to the large size of the dystrophin gene that is implicated in the disorder, making it a target for spontaneous mutations. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, July 17, 2013

How does MD affect muscles?[edit | edit source]

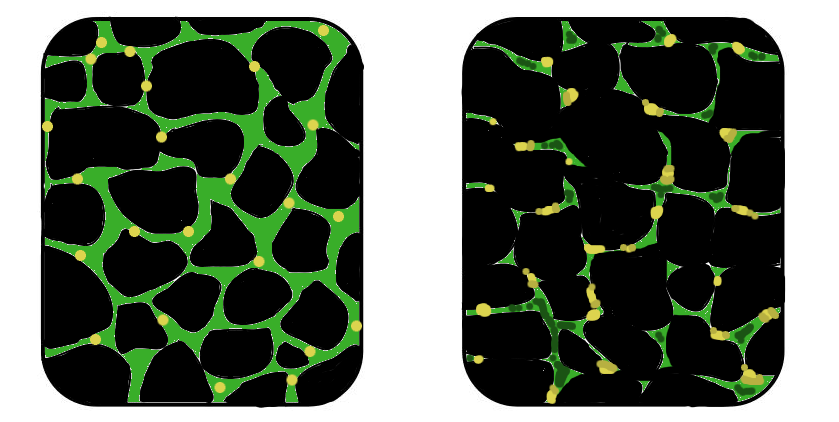

Muscles are made up of thousands of muscle fibers. Each fiber is actually a number of individual cells that have joined together during development and are encased by an outer membrane. Muscle fibers that make up individual muscles are bound together by connective tissue. Muscles are activated when an impulse, or signal, is sent from the brain through the spinal cord and peripheral nerves (nerves that connect the central nervous system to sensory organs and muscles) to the neuromuscular junction (the space between the nerve fiber and the muscle it activates). There, a release of the chemical acetylcholine triggers a series of events that cause the muscle to contract. The muscle fiber membrane contains a group of proteins—called the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex—which prevents damage as muscle fibers contract and relax. When this protective membrane is damaged, muscle fibers begin to leak the protein creatine kinase (needed for the chemical reactions that produce energy for muscle contractions) and take on excess calcium, which causes further harm. Affected muscle fibers eventually die from this damage, leading to progressive muscle degeneration. Although MD can affect several body tissues and organs, it most prominently affects the integrity of muscle fibers. The disease causes muscle degeneration, progressive weakness, fiber death, fiber branching and splitting, phagocytosis (in which muscle fiber material is broken down and destroyed by scavenger cells), and, in some cases, chronic or permanent shortening of tendons and muscles. Also, overall muscle strength and tendon reflexes are usually lessened or lost due to replacement of muscle by connective tissue and fat.

Are there other MD-like conditions?[edit | edit source]

There are many other heritable diseases that affect the muscles, the nerves, or the neuromuscular junction. Such diseases as inflammatory myopathy, progressive muscle weakness, and cardiomyopathy (heart muscle weakness that interferes with pumping ability) may produce symptoms that are very similar to those found in some forms of MD), but they are caused by different genetic defects. The differential diagnosis for people with similar symptoms includes congenital myopathy, spinal muscular atrophy, and congenital myasthenic syndromes. The sharing of symptoms among multiple neuromuscular diseases, and the prevalence of sporadic cases in families not previously affected by MD, often makes it difficult for people with MD to obtain a quick diagnosis. Gene testing can provide a definitive diagnosis for many types of MD, but not all genes have been discovered that are responsible for some types of MD. Some individuals may have signs of MD, but carry none of the currently recognized genetic mutations. Studies of other related muscle diseases may, however, contribute to what we know about MD.

How do the muscular dystrophies differ?[edit | edit source]

There are nine major groups of the muscular dystrophies. The disorders are classified by the extent and distribution of muscle weakness, age of onset, rate of progression, severity of symptoms, and family history (including any pattern of inheritance). Although some forms of MD become apparent in infancy or childhood, others may not appear until middle age or later. Overall, incidence rates and severity vary, but each of the dystrophies causes progressive skeletal muscle deterioration, and some types affect cardiac muscle. Duchenne MD is the most common childhood form of MD, as well as the most common of the muscular dystrophies overall, accounting for approximately 50 percent of all cases. Because inheritance is X-linked recessive (caused by a mutation on the X, or sex, chromosome), Duchenne MD primarily affects boys, although girls and women who carry the defective gene may show some symptoms. About one-third of the cases reflect new mutations and the rest run in families. Sisters of boys with Duchenne MD have a 50 percent chance of carrying the defective gene. Duchenne MD usually becomes apparent during the toddler years, sometimes soon after an affected child begins to walk. Progressive weakness and muscle wasting (a decrease in muscle strength and size) caused by degenerating muscle fibers begins in the upper legs and pelvis before spreading into the upper arms. Other symptoms include loss of some reflexes, a waddling gait, frequent falls and clumsiness (especially when running), difficulty when rising from a sitting or lying position or when climbing stairs, changes to overall posture, impaired breathing, lung weakness, and cardiomyopathy. Many children are unable to run or jump. The wasting muscles, in particular the calf muscles (and, less commonly, muscles in the buttocks, shoulders, and arms), may be enlarged by an accumulation of fat and connective tissue, causing them to look larger and healthier than they actually are (called pseudohypertrophy). As the disease progresses, the muscles in the diaphragm that assist in breathing and coughing may weaken. Affected individuals may experience breathing difficulties, respiratory infections, and swallowing problems. Bone thinning and scoliosis (curving of the spine) are common. Some affected children have varying degrees of cognitive and behavioral impairments. Between ages 3 and 6, children may show brief periods of physical improvement followed later on by progressive muscle degeneration. Children with Duchenne MD typically lose the ability to walk by early adolescence. Without aggressive care, they usually die in their late teens or early twenties from progressive weakness of the heart muscle, respiratory complications, or infection. However, improvements in multidisciplinary care have extended the life expectancy and improved the quality of life significantly for these children; numerous individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy now survive into their 30s, and some even into their 40s. Duchenne MD results from an absence of the muscle protein dystrophin. Dystrophin is a protein found in muscle that helps muscles stay healthy and strong. Blood tests of children with Duchenne MD show an abnormally high level of creatine kinase; this finding is apparent from birth. Becker MD is less severe than but closely related to Duchenne MD. People with Becker MD have partial but insufficient function of the protein dystrophin. There is greater variability in the clinical course of Becker MD compared to Duchenne MD. The disorder usually appears around age 11 but may occur as late as age 25, and affected individuals generally live into middle age or later. The rate of progressive, symmetric (on both sides of the body) muscle atrophy and weakness varies greatly among affected individuals. Many individuals are able to walk until they are in their mid-thirties or later, while others are unable to walk past their teens. Some affected individuals never need to use a wheelchair. As in Duchenne MD, muscle weakness in Becker MD is typically noticed first in the upper arms and shoulders, upper legs, and pelvis. Early symptoms of Becker MD include walking on one's toes, frequent falls, and difficulty rising from the floor. Calf muscles may appear large and healthy as deteriorating muscle fibers are replaced by fat, and muscle activity may cause cramps in some people. Cardiac complications are not as consistently present in Becker MD compared to Duchenne MD, but may be as severe in some cases. Cognitive and behavioral impairments are not as common or severe as in Duchenne MD, but they do occur. Congenital MD refers to a group of autosomal recessive muscular dystrophies that are either present at birth or become evident before age 2. They affect both boys and girls. The degree and progression of muscle weakness and degeneration vary with the type of disorder. Weakness may be first noted when children fail to meet landmarks in motor function and muscle control. Muscle degeneration may be mild or severe and is restricted primarily to skeletal muscle. The majority of individuals are unable to sit or stand without support, and some affected children may never learn to walk. There are three groups of congenital MD:

- merosin-negative disorders, where the protein merosin (found in the connective tissue that surrounds muscle fibers) is missing;

- merosin-positive disorders, in which merosin is present but other needed proteins are missing; and

- neuronal migration disorders, in which very early in the development of the fetal nervous system the migration of nerve cells (neurons) to their proper location is disrupted.

Defects in the protein merosin cause nearly half of all cases of congenital MD. People with congenital MD may develop contractures (chronic shortening of muscles or tendons around joints, which prevents the joints from moving freely), scoliosis, respiratory and swallowing difficulties, and foot deformities. Some individuals have normal intellectual development while others become severely impaired. Weakness in diaphragm muscles may lead to respiratory failure. Congenital MD may also affect the central nervous system, causing vision and speech problems, seizures, and structural changes in the brain. Some children with the disorders die in infancy while others may live into adulthood with only minimal disability. Distal MD, also called distal myopathy, describes a group of at least six specific muscle diseases that primarily affect distal muscles (those farthest away from the shoulders and hips) in the forearms, hands, lower legs, and feet. Distal dystrophies are typically less severe, progress more slowly, and involve fewer muscles than other forms of MD, although they can spread to other muscles, including the proximal ones later in the course of the disease. Distal MD can affect the heart and respiratory muscles, and idividuals may eventually require the use of a ventilator. Affected individuals may not be able to perform fine hand movement and have difficulty extending the fingers. As leg muscles become affected, walking and climbing stairs become difficult and some people may be unable to hop or stand on their heels. Onset of distal MD, which affects both men and women, is typically between the ages of 40 and 60 years. In one form of distal MD, a muscle membrane protein complex called dysferlin is known to be lacking. Although distal MD is primarily an autosomal dominant disorder, autosomal recessive forms have been reported in young adults. Symptoms are similar to those of Duchenne MD but with a different pattern of muscle damage. An infantile-onset form of autosomal recessive distal MD has also been reported. Slow but progressive weakness is often first noticed around age 1, when the child begins to walk, and continues to progress very slowly throughout adult life. Emery-Dreifuss MD primarily affects boys. The disorder has two forms: one is X-linked recessive and the other is autosomal dominant. Onset of Emery-Dreifuss MD is usually apparent by age 10, but symptoms can appear as late as the mid-twenties. This disease causes slow but progressive wasting of the upper arm and lower leg muscles and symmetric weakness. Contractures in the spine, ankles, knees, elbows, and back of the neck usually precede significant muscle weakness, which is less severe than in Duchenne MD. Contractures may cause elbows to become locked in a flexed position. The entire spine may become rigid as the disease progresses. Other symptoms include shoulder deterioration, toe-walking, and mild facial weakness. Serum creatine kinase levels may be moderately elevated. Nearly all people with Emery-Dreifuss MD have some form of heart problem by age 30, often requiring a pacemaker or other assistive device. Female carriers of the disorder often have cardiac complications without muscle weakness. Affected individuals often die in mid-adulthood from progressive pulmonary or cardiac failure. In some cases, the cardiac symptoms may be the earliest and most significant symptom of the disease, and may appear years before muscle weakness does. Facioscapulohumeral MD (FSHD) initially affects muscles of the face (facio), shoulders (scapulo), and upper arms (humera) with progressive weakness. Also known as Landouzy-Dejerine disease, this third most common form of MD is an autosomal dominant disorder. Most individuals have a normal life span, but some individuals become severely disabled. Disease progression is typically very slow, with intermittent spurts of rapid muscle deterioration. Onset is usually in the teenage years but may occur as early as childhood or as late as age 40. One hallmark of FSHD is that it commonly causes asymmetric weakness. Muscles around the eyes and mouth are often affected first, followed by weakness around the shoulders, chest, and upper arms. A particular pattern of muscle wasting causes the shoulders to appear to be slanted and the shoulder blades to appear winged. Muscles in the lower extremities may also become weakened. Reflexes are diminished, typically in the same distribution as the weakness. Changes in facial appearance may include the development of a crooked smile, a pouting look, flattened facial features, or a mask-like appearance. Some individuals cannot pucker their lips or whistle and may have difficulty swallowing, chewing, or speaking. In some individuals, muscle weakness can spread to the diaphragm, causing respiratory problems. Other symptoms may include hearing loss (particularly at high frequencies) and lordosis, an abnormal swayback curve in the spine. Contractures are rare. Some people with FSHD feel severe pain in the affected limb. Cardiac muscles are not usually affected, and significant weakness of the pelvic girdle is less common than in other forms of MD. An infant-onset form of FSHD can also cause retinal disease and some hearing loss. Limb-girdle MD (LGMD) refers to more than 20 inherited conditions marked by progressive loss of muscle bulk and symmetrical weakening of voluntary muscles, primarily those in the shoulders and around the hips. At least 5 forms of autosomal dominant limb-girdle MD (known as type 1) and 17 forms of autosomal recessive limb-girdle MD (known as type 2) have been identified. Some autosomal recessive forms of the disorder are now known to be due to a deficiency of any of four dystrophin-glycoprotein complex proteins called the sarcoglycans. Deficiencies in dystroglycan, classically associated with congenital muscular dystrophies, may also cause LGMD. The recessive LGMDs occur more frequently than the dominant forms, usually begin in childhood or the teenage years, and show dramatically increased levels of serum creatine kinase. The dominant LGMDs usually begin in adulthood. In general, the earlier the clinical signs appear, the more rapid the rate of disease progression. Limb-girdle MD affects both males and females. Some forms of the disease progress rapidly, resulting in serious muscle damage and loss of the ability to walk, while others advance very slowly over many years and cause minimal disability, allowing a normal life expectancy. In some cases, the disorder appears to halt temporarily, but progression then resumes. The pattern of muscle weakness is similar to that of Duchenne MD and Becker MD. Weakness is typically noticed first around the hips before spreading to the shoulders, legs, and neck. Individuals develop a waddling gait and have difficulty when rising from chairs, climbing stairs, or carrying heavy objects. They fall frequently and are unable to run. Contractures at the elbows and knees are rare but individuals may develop contractures in the back muscles, which gives them the appearance of a rigid spine. Proximal reflexes (closest to the center of the body) are often impaired. Some individuals also experience cardiomyopathy and respiratory complications, depending in part on the specific subtype. Intelligence remains normal in most cases, though exceptions do occur. Many individuals with limb-girdle MD become severely disabled within 20 years of disease onset. Myotonic dystrophy (DM1), also known as Steinert's disease and dystrophia myotonica, is another common form of MD. Myotonia, or an inability to relax muscles following a sudden contraction, is found only in this form of MD, but is also found in other non-dystrophic muscle diseases. People with DM1 can live a long life, with variable but slowly progressive disability. Typical disease onset is between ages 20 and 30, but childhood onset and congenital onset are well-documented. Muscles in the face and the front of the neck are usually first to show weakness and may produce a haggard, "hatchet" face and a thin, swan-like neck. Wasting and weakness noticeably affect forearm muscles. DM1 affects the central nervous system and other body systems, including the heart, adrenal glands and thyroid, eyes, and gastrointestinal tract. Other symptoms include cardiac complications, difficulty swallowing, droopy eyelids (called ptosis), cataracts, poor vision, early frontal baldness, weight loss, impotence, testicular atrophy, mild mental impairment, and increased sweating. Individuals may also feel drowsy and have an excess need to sleep. There is a second form of the disease that is similar to the classic form, but usually affects proximal muscles more significantly. This form is known as myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2). This autosomal dominant disease affects both men and women. Females may have irregular menstrual periods and are sometimes infertile. The disease may occur earlier and be more severe in successive generations. A childhood-onset form of myotonic MD may become apparent between ages 5 and 10. Symptoms include general muscle weakness (particularly in the face and distal muscles), lack of muscle tone, and mental impairment. A woman with DM1 can give birth to an infant with a rare congenital form of the disorder. Symptoms at birth may include difficulty swallowing or sucking, impaired breathing, absence of reflexes, skeletal deformities and contractures (such as club feet), and muscle weakness, especially in the face. Children with congenital myotonic MD may also experience mental impairment and delayed motor development. This severe infantile form of myotonic MD occurs almost exclusively in children who have inherited the defective gene from their mother, whose symptoms may be so mild that she is sometimes not aware that she has the disease until she has an affected child. The inherited gene defect that causes DM1 is an abnormally long repetition of a three-letter "word" in the genetic code. In unaffected people, the word is repeated a number of times, but in people with DM1, it is repeated many more times. This triplet repeat gets longer with each successive generation. The triplet repeat mechanism has now been implicated in at least 15 other disorders, including Huntington's disease and the spinocerebellar ataxias. Oculopharyngeal MD (OPMD) generally begins in a person's forties or fifties and affects both men and women. In the United States, the disease is most common in families of French-Canadian descent and among Hispanic residents of northern New Mexico. People first report drooping eyelids, followed by weakness in the facial muscles and pharyngeal muscles in the throat, causing difficulty swallowing. The tongue may atrophy and changes to the voice may occur. Eyelids may droop so dramatically that some individuals compensate by tilting back their heads. Affected individuals may have double vision and problems with upper gaze, and others may have retinitis pigmentosa (progressive degeneration of the retina that affects night vision and peripheral vision) and cardiac irregularities. Muscle weakness and wasting in the neck and shoulder region is common. Limb muscles may also be affected. Persons with OPMD may find it difficult to walk, climb stairs, kneel, or bend. Those persons most severely affected will eventually lose the ability to walk.

How are the muscular dystrophies diagnosed?[edit | edit source]

Both the individual's medical history and a complete family history should be thoroughly reviewed to determine if the muscle disease is secondary to a disease affecting other tissues or organs or is an inherited condition. It is also important to rule out any muscle weakness resulting from prior surgery, exposure to toxins, or current medications that may affect the person's functional status or rule out many acquired muscle diseases. Thorough clinical and neurological exams can rule out disorders of the central and/or peripheral nervous systems, identify any patterns of muscle weakness and atrophy, test reflex responses and coordination, and look for contractions. Various laboratory tests may be used to confirm the diagnosis of MD. Blood and urine tests can detect defective genes and help identify specific neuromuscular disorders. For example:

- Creatine kinase is an enzyme that leaks out of damaged muscle. Elevated creatine kinase levels may indicate muscle damage, including some forms of MD, before physical symptoms become apparent. Levels are significantly increased in the early stages of Duchenne and Becker MD. Testing can also determine if a young woman is a carrier of the disorder.

- The level of serum aldolase, an enzyme involved in the breakdown of glucose, is measured to confirm a diagnosis of skeletal muscle disease. High levels of the enzyme, which is present in most body tissues, are noted in people with MD and some forms of myopathy.

- Myoglobin is measured when injury or disease in skeletal muscle is suspected. Myoglobin is an oxygen-binding protein found in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. High blood levels of myoglobin are found in people with MD.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can detect some mutations in the dystrophin gene. Also known as molecular diagnosis or genetic testing, PCR is a method for generating and analyzing multiple copies of a fragment of DNA.

- Serum electrophoresis is a test to determine quantities of various proteins in a person's DNA. A blood sample is placed on specially treated paper and exposed to an electric current. The charge forces the different proteins to form bands that indicate the relative proportion of each protein fragment.

Exercise tests can detect elevated rates of certain chemicals following exercise and are used to determine the nature of the MD or other muscle disorder. Some exercise tests can be performed bedside while others are done at clinics or other sites using sophisticated equipment. These tests also assess muscle strength. They are performed when the person is relaxed and in the proper position to allow technicians to measure muscle function against gravity and detect even slight muscle weakness. If weakness in respiratory muscles is suspected, respiratory capacity may be measured by having the person take a deep breath and count slowly while exhaling. Genetic testing looks for genes known to either cause or be associated with inherited muscle disease. DNA analysis and enzyme assays can confirm the diagnosis of certain neuromuscular diseases, including MD. Genetic linkage studies can identify whether a specific genetic marker on a chromosome and a disease are inherited together. They are particularly useful in studying families with members in different generations who are affected. An exact molecular diagnosis is necessary for some of the treatment strategies that are currently being developed. Advances in genetic testing include whole exome and whole genome sequencing, which will enable people to have all of their genes screened at once for disease-causing mutations, rather than have just one gene or several genes tested at a time. Exome sequencing looks at the part of the individual’s genetic material, or genome, that “code for” (or translate) into proteins. Genetic counseling can help parents who have a family history of MD determine if they are carrying one of the mutated genes that cause the disorder. Two tests can be used to help expectant parents find out if their child is affected.

- Amniocentesis, done usually at 14-16 weeks of pregnancy, tests a sample of the amniotic fluid in the womb for genetic defects (the fluid and the fetus have the same DNA). Under local anesthesia, a thin needle is inserted through the woman's abdomen and into the womb. About 20 milliliters of fluid (roughly 4 teaspoons) is withdrawn and sent to a lab for evaluation. Test results often take 1-2 weeks.

- Chorionic villus sampling, or CVS, involves the removal and testing of a very small sample of the placenta during early pregnancy. The sample, which contains the same DNA as the fetus, is removed by catheter or a fine needle inserted through the cervix or by a fine needle inserted through the abdomen. The tissue is tested for genetic changes identified in an affected family member. Results are usually available within 2 weeks.

Diagnostic imaging can help determine the specific nature of a disease or condition. One such type of imaging, called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is used to examine muscle quality, any atrophy or abnormalities in size, and fatty

Search WikiMD

Ad.Tired of being Overweight? Try W8MD's physician weight loss program.

Semaglutide (Ozempic / Wegovy and Tirzepatide (Mounjaro / Zepbound) available.

Advertise on WikiMD

|

WikiMD's Wellness Encyclopedia |

| Let Food Be Thy Medicine Medicine Thy Food - Hippocrates |

Translate this page: - East Asian

中文,

日本,

한국어,

South Asian

हिन्दी,

தமிழ்,

తెలుగు,

Urdu,

ಕನ್ನಡ,

Southeast Asian

Indonesian,

Vietnamese,

Thai,

မြန်မာဘာသာ,

বাংলা

European

español,

Deutsch,

français,

Greek,

português do Brasil,

polski,

română,

русский,

Nederlands,

norsk,

svenska,

suomi,

Italian

Middle Eastern & African

عربى,

Turkish,

Persian,

Hebrew,

Afrikaans,

isiZulu,

Kiswahili,

Other

Bulgarian,

Hungarian,

Czech,

Swedish,

മലയാളം,

मराठी,

ਪੰਜਾਬੀ,

ગુજરાતી,

Portuguese,

Ukrainian

Medical Disclaimer: WikiMD is not a substitute for professional medical advice. The information on WikiMD is provided as an information resource only, may be incorrect, outdated or misleading, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Please consult your health care provider before making any healthcare decisions or for guidance about a specific medical condition. WikiMD expressly disclaims responsibility, and shall have no liability, for any damages, loss, injury, or liability whatsoever suffered as a result of your reliance on the information contained in this site. By visiting this site you agree to the foregoing terms and conditions, which may from time to time be changed or supplemented by WikiMD. If you do not agree to the foregoing terms and conditions, you should not enter or use this site. See full disclaimer.

Credits:Most images are courtesy of Wikimedia commons, and templates, categories Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY SA or similar.

Contributors: Prab R. Tumpati, MD