Muir–Torre syndrome

(Redirected from Cutaneous sebaceous neoplasms and keratoacanthomas multiple with gastrointestinal and other carcinomas)

| Muir–Torre syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synonyms | MTS |

| Pronounce | |

| Field | Oncology, Dermatology, Genetics |

| Symptoms | Sebaceous tumors, internal malignancies |

| Complications | Colorectal cancer, genitourinary cancers |

| Onset | Usually adulthood |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | |

| Causes | Genetic mutations in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 genes |

| Risks | Family history of Lynch syndrome |

| Diagnosis | Clinical presentation, genetic testing, immunohistochemistry |

| Differential diagnosis | Sporadic sebaceous tumors, other hereditary cancer syndromes |

| Prevention | Regular screening, genetic counseling |

| Treatment | Surgical excision, regular cancer surveillance |

| Medication | |

| Prognosis | Good with early detection and management |

| Frequency | Rare |

| Deaths | Usually related to complications from malignancies |

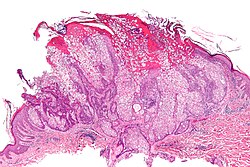

Muir–Torre syndrome (MTS) is a rare, hereditary autosomal dominant cancer syndrome, considered a subtype of Lynch syndrome (Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer, HNPCC). Individuals with this syndrome have an increased susceptibility to cancers of the colon, genitourinary tract, and distinct skin lesions, including keratoacanthomas and sebaceous tumors such as sebaceous adenoma, sebaceous epithelioma, and sebaceous carcinoma.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Characteristic features include:

- Presence of at least one sebaceous gland tumor (adenoma, epithelioma, or carcinoma)

- Occurrence of at least one internal malignancy, commonly colorectal or genitourinary cancers

Genetics[edit | edit source]

Muir–Torre syndrome is caused primarily by mutations in the MLH1, MSH2, and more recently identified MSH6 genes. These genes are critical for the DNA mismatch repair pathway. Mutations result in defective DNA repair mechanisms, increasing the risk of developing cancers.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis typically involves:

- Clinical evaluation of sebaceous skin tumors and internal malignancies

- Genetic testing for mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes

- Immunohistochemical analysis for mismatch repair proteins

- Application of the Amsterdam criteria, widely used to diagnose Lynch syndrome and Muir–Torre syndrome, which include:

- At least three relatives affected by Lynch-associated cancers (colorectal, endometrial, small bowel, ureter, renal pelvis)

- Cancer affecting at least two successive generations

- At least one individual diagnosed before age 50

- Exclusion of familial adenomatous polyposis

The Mayo Muir–Torre risk score was developed to enhance diagnostic accuracy, distinguishing true cases from sporadic sebaceous tumors.

Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment strategies involve:

- Surgical removal of skin lesions

- Regular screening and surveillance for internal malignancies (colonoscopies, genitourinary screenings)

- Genetic counseling for patients and their families

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

With appropriate management and regular surveillance, the prognosis for individuals with Muir–Torre syndrome can be favorable. Early detection and treatment of malignancies significantly improve outcomes.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Preventive measures focus on:

- Early genetic screening and counseling for at-risk families

- Frequent surveillance for early detection of malignancies

Muir–Torre syndrome remains a rare condition, requiring multidisciplinary care involving dermatologists, geneticists, oncologists, and surgeons.

Eponym[edit | edit source]

It is named for EG Muir and D Torre. A British physician, Muir noted a patient with many keratoacanthomas who went on to develop several internal malignancies at a young age. Torre presented his findings at a meeting of the New York Dermatologic Society.

See also[edit | edit source]

- List of cutaneous conditions

- List of cutaneous conditions associated with increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer

External links[edit | edit source]

| Tumors and associated structures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Metabolic disease: DNA replication and DNA repair-deficiency disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Search WikiMD

Ad.Tired of being Overweight? Try W8MD's physician weight loss program.

Semaglutide (Ozempic / Wegovy and Tirzepatide (Mounjaro / Zepbound) available.

Advertise on WikiMD

|

WikiMD's Wellness Encyclopedia |

| Let Food Be Thy Medicine Medicine Thy Food - Hippocrates |

Translate this page: - East Asian

中文,

日本,

한국어,

South Asian

हिन्दी,

தமிழ்,

తెలుగు,

Urdu,

ಕನ್ನಡ,

Southeast Asian

Indonesian,

Vietnamese,

Thai,

မြန်မာဘာသာ,

বাংলা

European

español,

Deutsch,

français,

Greek,

português do Brasil,

polski,

română,

русский,

Nederlands,

norsk,

svenska,

suomi,

Italian

Middle Eastern & African

عربى,

Turkish,

Persian,

Hebrew,

Afrikaans,

isiZulu,

Kiswahili,

Other

Bulgarian,

Hungarian,

Czech,

Swedish,

മലയാളം,

मराठी,

ਪੰਜਾਬੀ,

ગુજરાતી,

Portuguese,

Ukrainian

Medical Disclaimer: WikiMD is not a substitute for professional medical advice. The information on WikiMD is provided as an information resource only, may be incorrect, outdated or misleading, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Please consult your health care provider before making any healthcare decisions or for guidance about a specific medical condition. WikiMD expressly disclaims responsibility, and shall have no liability, for any damages, loss, injury, or liability whatsoever suffered as a result of your reliance on the information contained in this site. By visiting this site you agree to the foregoing terms and conditions, which may from time to time be changed or supplemented by WikiMD. If you do not agree to the foregoing terms and conditions, you should not enter or use this site. See full disclaimer.

Credits:Most images are courtesy of Wikimedia commons, and templates, categories Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY SA or similar.

Contributors: Deepika vegiraju, Prab R. Tumpati, MD