Adenoma

| Adenoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synonyms | |

| Pronounce | N/A |

| Specialty | N/A |

| Symptoms | Often asymptomatic, may cause hormonal imbalance if functional |

| Complications | Potential progression to adenocarcinoma |

| Onset | Varies depending on type and location |

| Duration | Indeterminate, may remain stable or progress |

| Types | Tubular adenoma, villous adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma |

| Causes | Genetic mutations, environmental factors |

| Risks | Age, family history, diet, smoking |

| Diagnosis | Biopsy, endoscopy, imaging studies |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma, polyp |

| Prevention | Regular screening, healthy diet, avoiding smoking |

| Treatment | Surgical removal, endoscopic resection |

| Medication | None specific, may use hormonal therapy if functional |

| Prognosis | Generally good if benign, risk of malignancy varies |

| Frequency | Common, varies by type and location |

| Deaths | Rare, unless progresses to malignancy |

Benign glandular tumors with potential malignant transformation

| Adenoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synonyms | Adenomatous tumor |

| Pronounce | |

| Field | Oncology, Pathology, Endocrinology, Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Often asymptomatic; may cause hormonal imbalance, obstruction, pain |

| Complications | Malignant transformation, bleeding, organ dysfunction |

| Onset | Variable; often detected in adults |

| Duration | Chronic (often lifelong surveillance required) |

| Types | Colorectal, pituitary, thyroid, adrenal, hepatic, renal, sebaceous |

| Causes | Genetic mutations, hormonal imbalance, environmental factors |

| Risks | Age, genetics, obesity, hormonal therapy, radiation exposure |

| Diagnosis | Clinical evaluation, imaging, laboratory tests, biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyperplastic polyps, adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors |

| Prevention | Lifestyle modifications, genetic screening |

| Treatment | Surveillance, endoscopic removal, surgical excision, medical therapy |

| Medication | Hormone suppressants, antithyroid medications, dopamine agonists |

| Prognosis | Generally good; dependent on type, size, and malignant risk |

| Frequency | Common (colorectal adenomas); other types vary |

| Deaths | Rare, usually due to malignant transformation or complications |

Adenoma is a type of benign tumor originating from glandular epithelial cells. Although adenomas themselves are benign, some possess the potential to progress into malignant tumors (adenocarcinoma). They commonly affect various glandular organs, including the colon, pituitary gland, thyroid gland, adrenal gland, liver, and kidney. Understanding their characteristics, potential complications, and management strategies is vital for early detection and treatment.

Definition and Characteristics[edit | edit source]

An adenoma arises from glandular epithelial tissue, forming a well-defined, localized mass. Despite their benign nature, adenomas can cause complications by:

- Compressing nearby structures (mass effect)

- Producing excess hormones (functional adenomas)

- Potentially transforming into malignant adenocarcinoma (notably colorectal adenomas)

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The frequency and clinical significance of adenomas vary by organ:

- Colorectal adenomas: Common in adults >50 years; precursors to colorectal cancer.

- Pituitary adenomas: Account for 10–15% of intracranial tumors.

- Thyroid adenomas: Frequent in women; detected as thyroid nodules.

- Hepatic adenomas: Rare; linked to oral contraceptive use.

Clinical Significance[edit | edit source]

Adenomas can significantly impact health due to:

- Hormonal imbalance: Functional adenomas can cause endocrine disorders (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome, hyperthyroidism).

- Obstruction: Large adenomas in the colon may cause bowel obstruction.

- Malignant potential: Particularly colorectal adenomas that can transform into colorectal cancer.

- Early identification and management are essential to reduce morbidity.

Types of Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Adenomas vary by anatomical location and behavior:

Colorectal Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Common precursors to colorectal cancer; subtypes include:

Pituitary Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Arise in the pituitary gland; subtypes include:

- Prolactinoma

- Growth hormone-secreting adenoma

- ACTH-secreting adenoma

- Non-functioning adenomas

Thyroid Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Often solitary nodules arising from follicular cells; subtypes include:

Adrenal Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Occur in adrenal cortex; may produce hormones (e.g., cortisol or aldosterone):

- Functioning adenomas (Cushing’s syndrome, Conn’s syndrome)

Hepatic Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Benign liver tumors associated with oral contraceptive use; risk of hemorrhage or malignant transformation.

Renal Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Small benign kidney tumors; usually incidental findings.

Sebaceous Adenomas[edit | edit source]

Associated with sebaceous glands; linked to Muir-Torre syndrome.

Causes and Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Adenomas develop due to genetic mutations, hormonal disturbances, and environmental factors:

- Genetic conditions (e.g., Familial adenomatous polyposis, Multiple endocrine neoplasia)

- Hormonal imbalances (pituitary, thyroid, adrenal adenomas)

- Diet and obesity (colorectal adenomas)

- Oral contraceptives (hepatic adenomas)

- Radiation exposure (thyroid adenomas)

Symptoms and Complications[edit | edit source]

Symptoms depend on adenoma location and hormone secretion:

- Colorectal adenomas: Rectal bleeding, bowel habit changes

- Pituitary adenomas: Vision changes, hormonal imbalance

- Thyroid adenomas: Hyperthyroidism, neck lump

- Adrenal adenomas: Cushing’s or Conn’s syndrome

- Hepatic adenomas: Abdominal pain, risk of bleeding

- Renal adenomas: Usually asymptomatic

Complications include malignant transformation, organ obstruction, hormonal disturbances, and bleeding.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis involves:

- Clinical evaluation: History, physical exam

- Imaging: Colonoscopy, ultrasound, MRI, CT

- Laboratory tests: Hormone levels, tumor markers

- Histopathology: Biopsy confirms diagnosis

Treatment and Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment varies by adenoma type and risk factors:

- Observation: Small, asymptomatic adenomas

- Endoscopic removal: Colorectal polyps

- Surgical excision: Large or high-risk adenomas

- Medical therapy: Hormone-suppressing medications for pituitary and adrenal adenomas

Long-term monitoring is often required due to recurrence risk.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Prognosis depends on adenoma type and malignant potential:

- Generally favorable with early detection and treatment

- High-risk adenomas require ongoing surveillance to prevent cancer progression

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Preventive strategies include lifestyle modifications, regular screenings (colonoscopy), genetic counseling, and hormonal regulation.

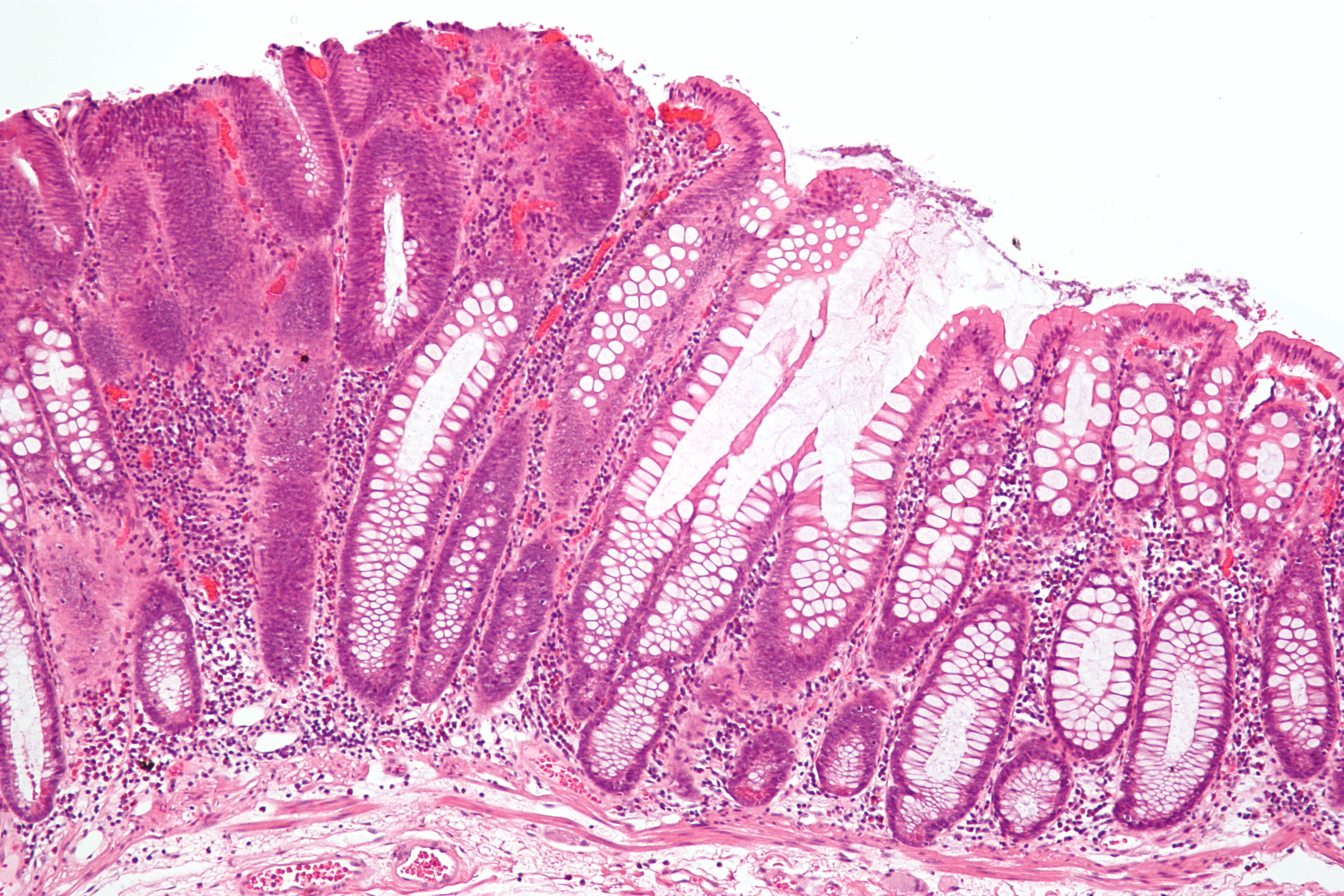

Gallery[edit | edit source]

See also[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

American Cancer Society – Adenomas Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD)

| Overview of tumors, cancer and oncology | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Endocrine disorders | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This endocrine disorder-related article is a stub.

|

Transform your life with W8MD's budget GLP1 injections from $125

W8MD offers a medical weight loss program NYC and a clinic to lose weight in Philadelphia. Our W8MD's physician supervised medical weight loss centers in NYC provides expert medical guidance, and offers telemedicine options for convenience.

Why choose W8MD?

- Comprehensive care with FDA-approved weight loss medications including:

- loss injections in NYC both generic and brand names:

- weight loss medications including Phentermine, Qsymia, Diethylpropion etc.

- Accept most insurances for visits or discounted self pay cost.

- Generic weight loss injections starting from just $125.00 for the starting dose

- In person weight loss NYC and telemedicine medical weight loss options in New York city available

- Budget GLP1 weight loss injections in NYC starting from $125.00 biweekly with insurance!

Book Your Appointment

Start your NYC weight loss journey today at our NYC medical weight loss, and Philadelphia medical weight loss Call (718)946-5500 for NY and 215 676 2334 for PA

Search WikiMD

Ad.Tired of being Overweight? Try W8MD's NYC physician weight loss.

Semaglutide (Ozempic / Wegovy and Tirzepatide (Mounjaro / Zepbound) available. Call 718 946 5500.

Advertise on WikiMD

|

WikiMD's Wellness Encyclopedia |

| Let Food Be Thy Medicine Medicine Thy Food - Hippocrates |

Translate this page: - East Asian

中文,

日本,

한국어,

South Asian

हिन्दी,

தமிழ்,

తెలుగు,

Urdu,

ಕನ್ನಡ,

Southeast Asian

Indonesian,

Vietnamese,

Thai,

မြန်မာဘာသာ,

বাংলা

European

español,

Deutsch,

français,

Greek,

português do Brasil,

polski,

română,

русский,

Nederlands,

norsk,

svenska,

suomi,

Italian

Middle Eastern & African

عربى,

Turkish,

Persian,

Hebrew,

Afrikaans,

isiZulu,

Kiswahili,

Other

Bulgarian,

Hungarian,

Czech,

Swedish,

മലയാളം,

मराठी,

ਪੰਜਾਬੀ,

ગુજરાતી,

Portuguese,

Ukrainian

Medical Disclaimer: WikiMD is not a substitute for professional medical advice. The information on WikiMD is provided as an information resource only, may be incorrect, outdated or misleading, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Please consult your health care provider before making any healthcare decisions or for guidance about a specific medical condition. WikiMD expressly disclaims responsibility, and shall have no liability, for any damages, loss, injury, or liability whatsoever suffered as a result of your reliance on the information contained in this site. By visiting this site you agree to the foregoing terms and conditions, which may from time to time be changed or supplemented by WikiMD. If you do not agree to the foregoing terms and conditions, you should not enter or use this site. See full disclaimer.

Credits:Most images are courtesy of Wikimedia commons, and templates, categories Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY SA or similar.

Contributors: Kondreddy Naveen, Prab R. Tumpati, MD